Many working in radio, including broadcast journalists, are pretty awful at spelling and grammar. I’m not perfect so don’t shoot me down if I make a mistake in this post…(though I am totally asking for it).

Plenty struggle with the ol’ spelling thing, especially when working under pressure or at speed. That’s fine. But I’ve also met plenty who think it’s ok to be lax because it’s ‘just for radio’. This seems to make them more likely not to check what they’ve written or to be lazy about trying to improve.

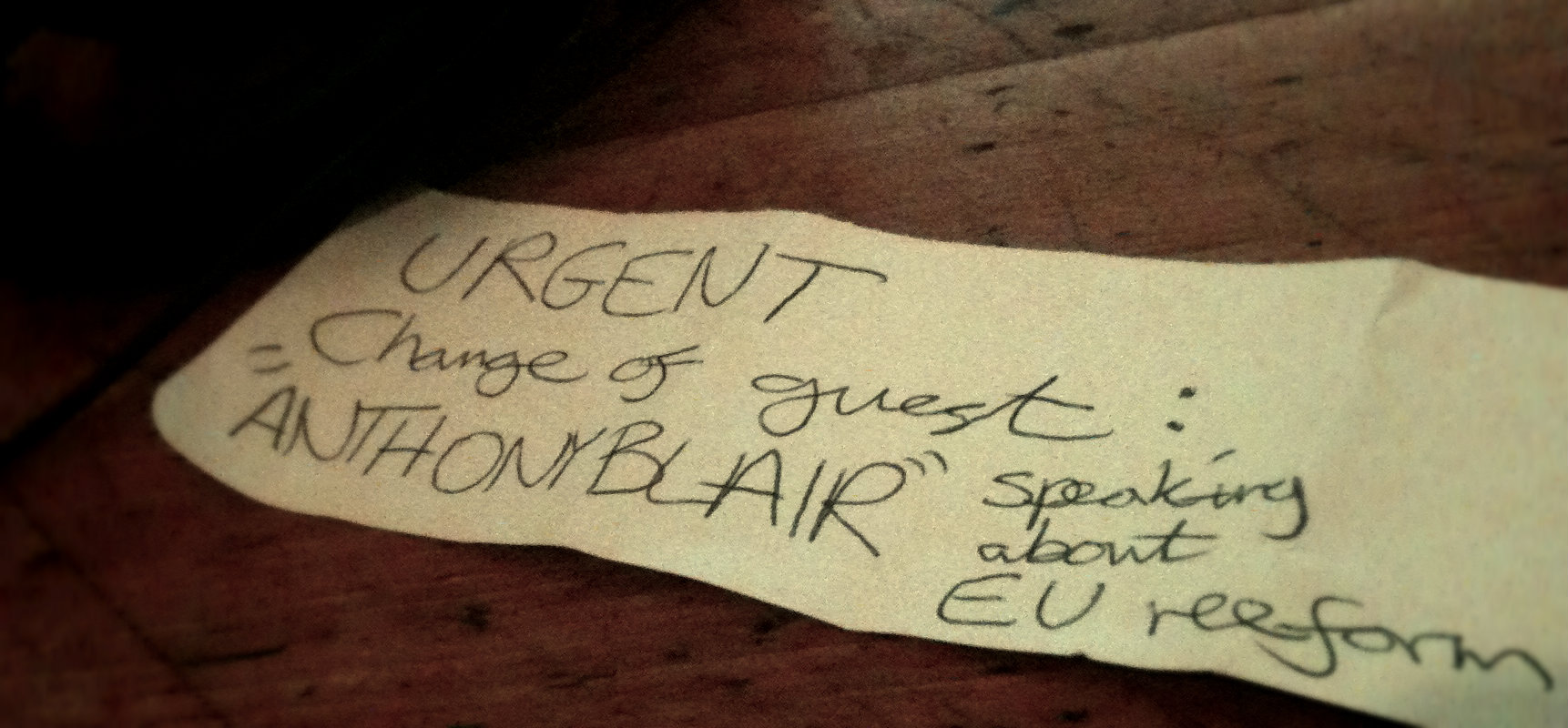

I’m including here spelling accuracy – that is – making sure you’re spelling people’s names correctly and getting details like job-titles perfect.

Just cos’ your working in radio its, not ok too get the SPAG all bad.

There are many reasons why, but here are just a few.

Social media

Twitter and Facebook are the obvious examples.

You write up some research on a music track for radio-play and spell the artist’s name wrong. Someone else could have a look at what you’ve done and tweet that.

You get the spelling wrong of a place name in a news bulletin. Before you know it someone’s looked at your script and tweeted it from your station’s official account.

You may work in radio but it’s increasingly likely that you’ll also write tweets and Facebook messages on official accounts yourself. Sloppy spelling, missing capital letters and strange punctuation makes your brand look rubbish, unprofessional and less authoritative, perhaps especially if it’s journalism-based.

Who knows where your words will end up

This is especially true of any organisation with multiple outlets, but my example is specific to the BBC, where I have the most experience.

We use a shared bit of software across all of BBC News. Anyone can read what I write in a radio script. I can read the scripts of others. And you’ve no idea where your words could end up. Once you’ve saved something in a ‘greened’ script (ie. ready for broadcast) it’s assumed that it encompasses all the BBC values of accuracy.

Let’s say I’m working in an empty BBC newsroom for a local radio station on a Sunday evening when there’s a MASSIVE local fire. I write a quick bit of copy for the regional news bulletin. All I want to do is be the first, the quickest with the information. In my three lines I misspell the name of the fire officer who told me they were “working hard to control the fire”, because I don’t have time to check the spelling. I know how it’s pronounced so I give it my best guess, because it’s ‘just for radio’.

Despite the fact I’m sitting alone in a small office, and it’s been successfully read on air to a few thousand people, suddenly what I’ve written starts appearing elsewhere. There it is on the ticker on the BBC News Channel. Then BBC Breaking News have tweeted the quote. Then BBC News Online have written an article. Then it’s on 5Live and they’re tweeting it. And so on. Suddenly something with the wrong spelling has spread to the entire BBC network.

Sight-reading on air

A presenter reading stuff on air from a script they’ve never seen before is called sight-reading.

Whether you’re a producer, journalist, broadcast assistant or manager: mess up your spelling and grammar, and sight-reading becomes a whole lot more difficult for the presenter. What goes out on air can then sound a whole lot worse. And someone probably gets annoyed at you.

Even if what you’ve written sounds phonetically right, it can mess up the train of thought and lead to awkward uncertainty when read on air. ‘Their’ instead of ‘there’ and ‘its’ instead of ‘it’s’ suddenly changes the meaning of a sentence and to a shrewd presenter makes it a lot more difficult to make sense of a sentence.

And an misplaced, comma can make a sentence, sound rediculous when, read, allowed.

Would you have read that last sentence out loud perfectly the first time you saw it, if you were also on air at the time?

What others think of you

I generally find those working in radio to be helpful, supportive and accommodating, but equally ruthless when help and support is not deserved.

If you struggle with spelling and grammar and say so, or perhaps do your best despite dyslexia, no-one’s going to mind. But if you’re of the opinion that it’s not a top priority because ‘it’s just radio’ you’ll be judged pretty quickly by some colleagues, bosses and potential employers.

If in doubt, take your time, double-check what you’ve written, and don’t worry about asking someone else to check it too. Someone can make a snap decision about your ability simply based on how you’ve written an email to them asking about work experience. If you’re continually making mistakes working as a broadcast journalist or senior producer the damage can be worse.