That’s a sentiment which could well be echoed by anyone who feels that TV and radio news bulletins and programme cues often sound like formulaic, uncreative pieces of churnalism.

I mean it could be. It might not be. I’m just guessing.

Anyway, see what I did there? My opening paragraph was a bit boring and generic so I headlined the piece with the trashy top-line ‘I hate journalism’. I apologise if at this stage you feel cheated into reading this. But that’s the point. It was a cheap tactic.

I don’t hate journalism. I’d actually like to share a few thoughts about my love/hate relationship with the ‘delayed drop’.

The delayed drop

A delayed drop is a technique you’ll be all too familiar with when you hear it (and read it – but I’ll talk here about broadcast journalism rather than print). Basically it’s when the crux of the story is delivered after something a little more sensational.

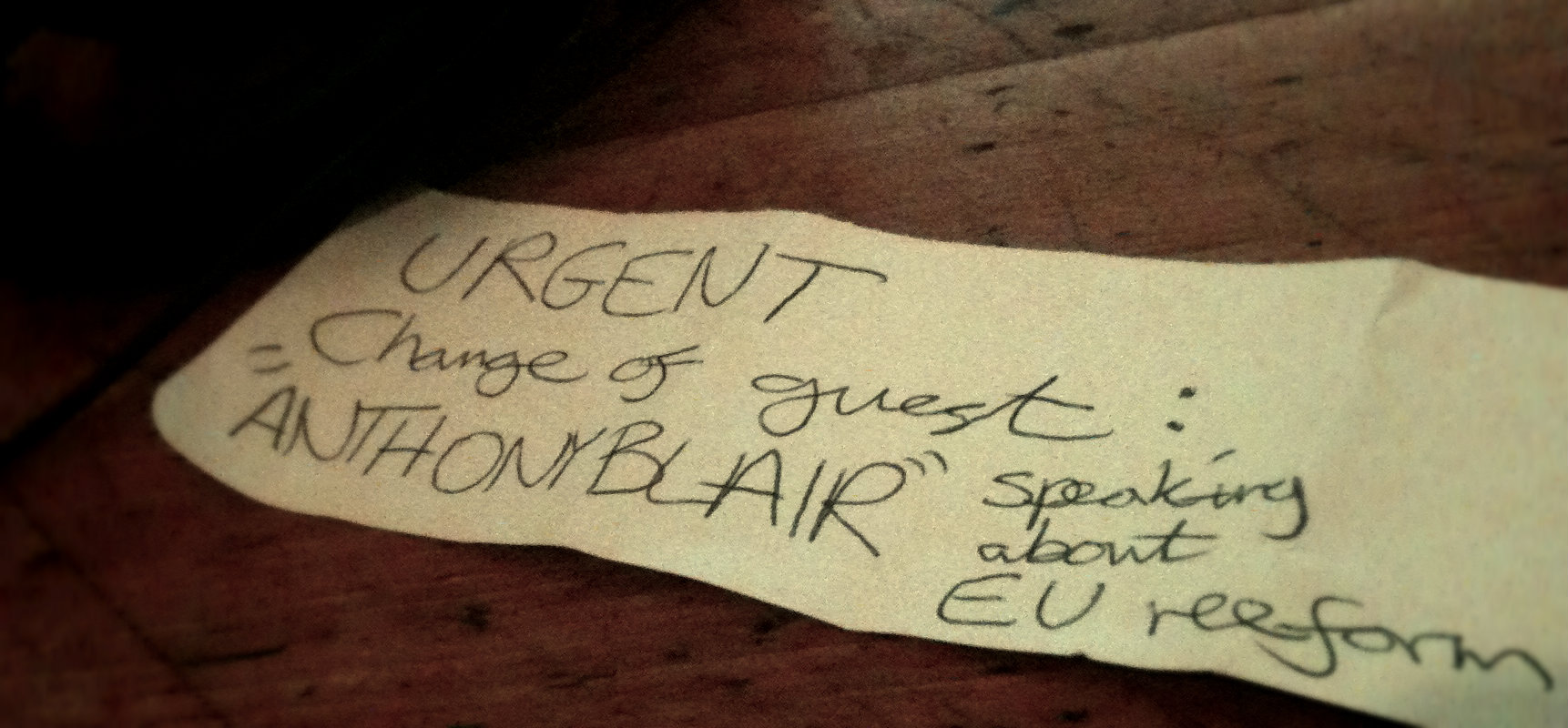

You can just imagine this news bulletin:

It’s been described as the most dramatic shake-up of the system for years.

Today, the pensions minister announced a radical change to state pensions…

The top-line is just a sexed-up tease; the detail follows in the second line. This sort of delayed drop seems to be ubiquitous. You can’t escape it. However, it’s a relatively gentle example. What sometimes grieves me more is when a direct quote is used:

Piers Morgan should be deported because, among other things, he’s a hatchet man of the New World Order.

Those are the views of one pro-gun American radio talk-show host who came to blows with the former British newspaper editor when interviewed on Piers Morgan’s CNN programme.

If that story arrived out of context right after a piece about a happy dolphin that had been saved, you can see how it might grab your attention.

You can basically take any old dramatic quote and shamelessly spice up your copy by making the quote your top-line.

Love*

As I say I have a love/hate relationship with these sorts of delayed drops.

I think it’s good to have varied copy. Sometimes you really can use them to entice a listener or viewer in to the story. Sometimes you can use the direct quote angle to slap someone in the face with a shocking statement or opinion out of the blue to grab their attention, before delivering the finer details.

It’s more interesting to use a delayed drop here and there than to never use them, but…

Hate

…they’re horribly overused. That’s my problem with them

If someone’s written a news story with a delayed drop, known they’ve done it, and have decided why that’s the best way to deliver the story, fine. So long as they’re not doing it too often.

The trouble is it too often sounds to me like a knee-jerk reaction to spice-up a boring story in an incredibly un-spicy and lazy way, or it just sounds like someone’s following a formula they were taught in journalism school.

If you go back to listening to news bulletins with a heightened awareness of the delayed drop after reading this, it won’t be long until you hear one. And the more commonplace the delayed drop becomes the less useful and less creative journalistic tool it becomes.

If your delayed drop sounds generic and boring, perhaps you should just face the fact the story isn’t incredible and just write it straight. Save the drop for another day.

* I perhaps wrote too much in defence of the delayed drop, because I want to cover my own back knowing that I have used them in the past, and will in the future. In honesty…I mostly hate them.